Understanding how your brain is wired can transform shame into compassion.

When I first began learning about ADHD, I thought it meant I just had to “try harder” to focus — that I needed more discipline, more willpower, more organization.

But the more I read, listened, and observed (in myself and in others), the clearer it became: this wasn’t a moral failure or character defect. It was wiring.

Confession.

I’m a closet nerd. I love science, especially brain science. So grab your notebook (because yes, I’ll be quizzing you later) and let’s take a look at what’s actually happening under the surface.

Dr. Russell Barkley and other researchers have shown that ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder, not a behavioral problem. That means it’s rooted in how the brain develops and communicates — especially in regions responsible for regulation, timing, and reward.

When Knowledge Meets Healing

I went thirty years living with ADHD before I knew I had it.

I accumulated experience after experience of failure, limitation, and social catastrophes without understanding why. It had to be me, right? Something is wrong with me.

Blind to the ADHD, these experiences infected my identity. “I’m just not good enough… what’s the point of trying… I might as well stop wasting my time trying to change and avert that energy to covering it up.” I masked my confusion, embarrassment, even shame, with a careless attitude.

There was a change in middle school — a shift from an eager, earnest child who felt sad by rejection to an angry adolescent who led with “I don’t care.” I masked by not caring about authority, grades, or anything conventionally valued that might expose me to embarrassment if I didn’t fit the mold.

I remember moments of feeling proud in detention because I had talked back to a teacher in front of the class. The anger and outward dismissiveness protected me. But ultimately, it moved me further and further from who I was and what I was feeling.

I learned to adapt to the confusion and blindness of ADHD. It wasn’t healthy, as we’d define health. It was survival.

Then, through a series of events over the course of my life, I discovered this missing piece of my story — and everything changed. Understanding ADHD didn’t just explain my behavior; it began to heal my heart.

From feeling rejected by others in school, to learning how to reject myself, the healing process worked backwards.

Once I was able to see what I was blind to, awareness gave me the ability to understand myself in a way I never could before. And once we can see something, we can understand it. Once we can understand it, we can love it.

That’s what happened to me.

I could see the ADHD now. Things made sense in retrospect.

The struggles I kept running into, the relational ruptures, the self-blame — they all had context.

And when I could explain it to others, they could understand it too. And once others could see and understand it, it became easier to love me, as I learned to love myself.

I no longer feel threatened by my ADHD.

Sure, it’s still annoying, inconvenient, and sometimes embarrassing — but that’s because I’m still pilgrimaging. And I’ve learned that these struggles don’t have to stop my life; they’ve become reminders that I was never meant to be self-sufficient.

The Lord will always want me to know He is there. That He is my Savior. That I am loved and lovable.

Because of this, I don’t have to be afraid of my shortcomings. “Oh happy fault”—through these weaknesses, doors open for me to love others and allow myself to be loved, truly.

Because loving when it’s easy is good, but there’s a greater excellence in choosing love when it takes effort. ADHD helps keep me on track for that kind of love.

I am so aware of how often I fall short despite my efforts — which serves as a constant reminder that I’m not supposed to be doing all this on my own.

The Three Big Players

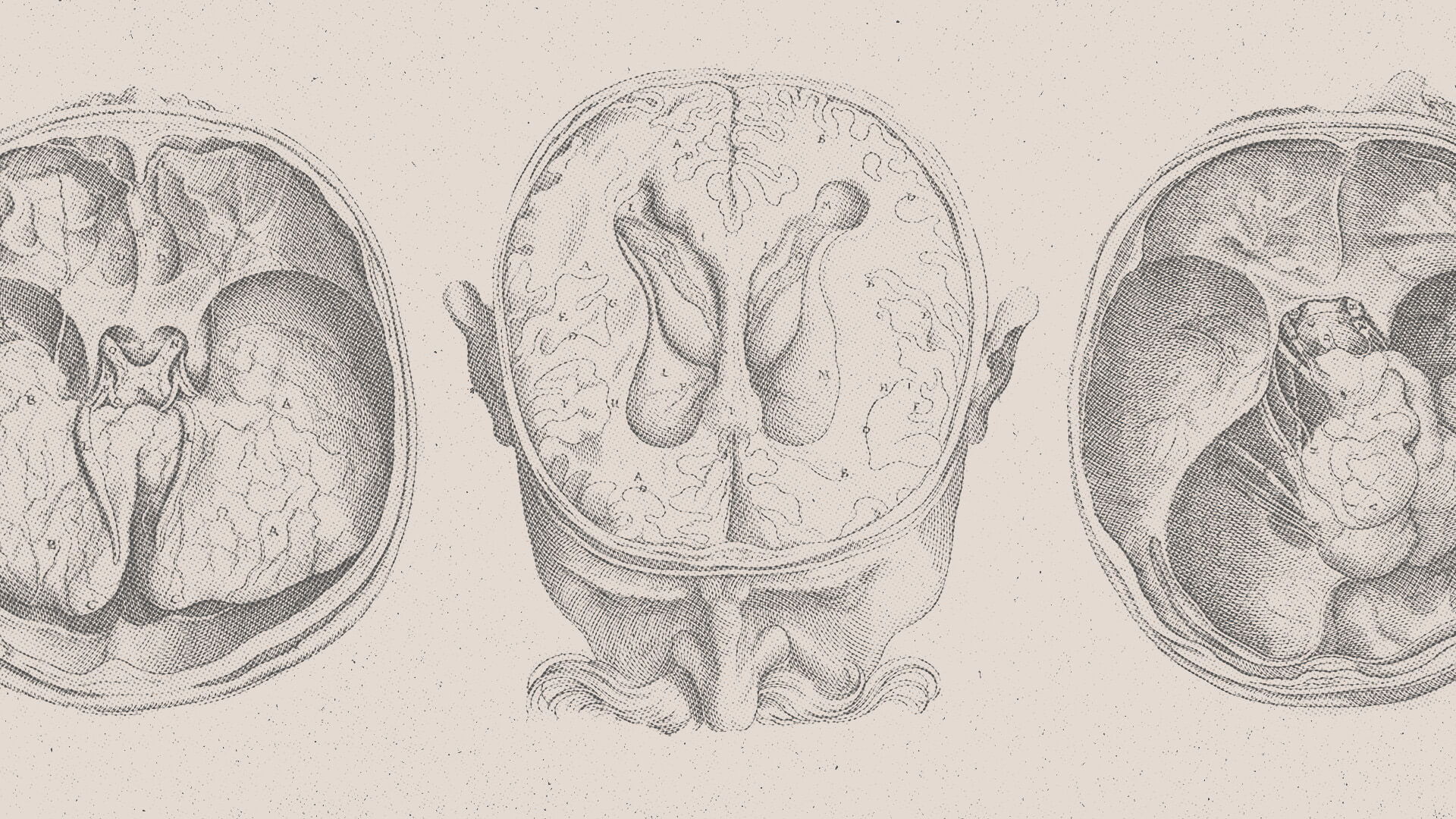

Think of the brain as a company.

There are executives, managers, and workers — all meant to communicate clearly and keep the system running smoothly. In ADHD, the communication lines between these levels are… fuzzy.

Here’s what’s going on:

1. The Prefrontal Cortex — The Capable CEO That Keeps Losing Connection

This region, right behind your forehead, is the “executive” of the brain — responsible for planning, decision-making, focus, inhibition, and self-control.

In ADHD, the prefrontal cortex is under-activated and develops more slowly. That means it takes longer for the brain to fully mature in the areas that help with organizing, prioritizing, and following through.

It’s like having a capable CEO who keeps losing Wi-Fi. The ideas are there, but the connection flickers just when it’s most needed.

When this happens:

- Focus shifts rapidly from one stimulus to another.

- Tasks that require sustained effort feel painful or boring.

- The “pause” button between thought and action doesn’t always click.

This isn’t irresponsibility — it’s a difference in activation.

What “Delayed Development” Actually Means

Dr. Barkley explains that the ADHD brain develops about 30% more slowly in its executive regions than a neurotypical brain.

That delay doesn’t mean permanent immaturity — it means the wiring that manages time, planning, and inhibition takes longer to reach full efficiency.

To visualize this:

- A 6-year-old with ADHD may function more like a 4-year-old in self-control and emotional regulation.

- A 25-year-old may rely on planners, reminders, and accountability like a neurotypical 17- or 18-year-old.

- Even a 50-year-old may still need external scaffolds under stress — not from lack of growth, but because their executive systems require conscious support.

It’s not about intelligence or effort; it’s about brain development and integration.

The ADHD brain eventually catches up, but it never fully automates regulation the way a neurotypical brain might. That’s why structure remains essential across the lifespan.

2. The Basal Ganglia — The Gatekeeper of Movement and Motivation

If the prefrontal cortex is the CEO, the basal ganglia are the gatekeepers — deciding which thoughts or actions get through and which stay on hold.

In ADHD, these gatekeepers don’t filter efficiently. Too much information floods in at once.

Sounds, sights, feelings, memories — all compete for attention simultaneously.

Because dopamine levels in this region tend to be lower, motivation gets hijacked.

The brain struggles to feel reward until the pressure or excitement is high.

That’s why it’s easier to work under a deadline than on a slow, steady project. While it looks and feels like procrastination, it is best understood as neurochemistry waiting for enough stimulation to “turn on.”

3. The Cerebellum — The Timekeeper

Tucked at the base of the brain, the cerebellum coordinates movement, rhythm, and timing — not just physical timing, but mental timing too.

Barkley and other researchers believe the cerebellum plays a key role in ADHD’s time blindness.

When this region is under-connected, the internal sense of time — “how long this will take,” “when I started,” “how far I’ve come” — becomes unreliable. That’s why you can sit down for “five minutes” and look up an hour later, or underestimate how long it takes to get out the door.

It’s not poor planning; it’s a literal gap in the brain’s ability to feel the flow of time.

The Chemistry of Focus: Dopamine and Norepinephrine

Dopamine is the brain’s messenger of motivation, reward, and satisfaction. It’s what gives you the sense of “this matters — keep going.” When you finish a task, laugh with someone you love, or check off a to-do, dopamine releases that wave of reinforcement that says, “Do that again.”

It also helps the prefrontal cortex stay engaged — it literally fuels focus and persistence.

Without enough dopamine, the signal between brain regions weakens, making sustained effort feel uncomfortable or empty.

How Dopamine Works Differently in ADHD

In a neurotypical brain, dopamine is released steadily across tasks, keeping motivation consistent.

In ADHD, dopamine release is lower and less predictable. That means the brain often feels under-stimulated — searching for novelty or emotion to wake it up.

So the ADHD brain is interest-based, not importance-based.

A neurotypical person might think, “I should do my taxes because they’re due soon.”

Someone with ADHD feels no internal spark until there’s an immediate reason — a deadline, a crisis, a surge of urgency.

That’s why hyperfocus feels so satisfying — it’s the moment the brain finally “clicks on.”

Norepinephrine, which works alongside dopamine, regulates alertness and readiness.

When dopamine motivates, norepinephrine mobilizes.

In ADHD, both tend to run low, leaving the brain underpowered until urgency or novelty triggers a spike.

That’s why stimulant medications don’t “speed you up”; they stabilize this system, helping the brain find the middle ground between under-stimulated and overwhelmed.

Seeing It Through a Faith Lens

Understanding the brain doesn’t erase the struggle — but it transforms how we participate in it.

We were always going to have to carry the cross. And for those with ADHD, this is part of that.

The cross becomes the pathway to a greater love of self, others, and ultimately, of God.

It may seem like a tall order, but the goal is to befriend the cross — to choose it, to embrace it, to bless it, and ultimately, to fall in love with Love Himself.

The limitations of ADHD don’t have to be sources of shame when they can become sources of love — where you allow others to love you and allow the struggle to stretch your heart to love others.

I hope this reflection blesses you and gives you a deeper understanding of yourself, of those in your life who may be struggling with ADHD, and of the hope that life can still be rich, meaningful, and beautiful even within struggle.

We can’t escape the cross, but we can cultivate a spirit of curiosity and openness — to see the deeper meaning behind why we’ve been given the crosses we carry. There is always a reason why we suffer in the ways that we do. It is always meant to lead us toward a greater experience of love.

And we’re not made to do this alone.

Not made to suffer alone.

Not made to pilgrimage alone.

We need each other.

If this touches you in that deep, familiar place — you know the one I’m talking about — and you’re ready to stop suffering alone, I encourage you to reach out. Reach out to those around you. Reach out to us. This is why we are here. There should be no obstacle between you and the help you need.

In addition to our daily accompaniment, we’ve now opened a Catholic ADHD Group on Facebook — a community for support, understanding, and friendship.

I’d love for you to come join us there.

God bless you,

Teresa Violette